Why are we afraid of robots? Part 1 - Robots as containers for those things we fear about ourselves

First in a series where I look at my academic work differently.

So, with the introductions and explanations out of the way…

I want to discuss some of the work I did early in my research on robotics. The origin of this work you can read about here, though the short version is that my friend, the brilliant Professor Tony Prescott, once just asked me, ‘Why are we afraid of robots?’ It was back in the days when there was a lot of public backlash on the research in genetically-modified foods, so there were a lot of concerns amongst researchers that despite all of the Brilliant New Ideas (C) that Clever People had come up with to Make the World A Better Place (TM), they hadn’t stopped to think about whether people actually wanted these things.

But, as Henry Ford famously-maybe said, if he’d asked people what they wanted, they would have said a faster horse. So sometimes maybe we can just bulldoze through the fear, and wait for people — or ‘people’, whoever they are — to catch up with us. But yes, I know mentioning Ford in this context is dangerous, given we have our own oligarchic-leaning fascists to worry about today.

But another important piece of the puzzle — and the direction I wanted to take the question — is trying to understand how technology interacts with our imagination, and how our own anxieties about ourselves and who we are lead us to create monsters that are just really versions of ourselves.

I’ve touched on this paper a few times in my posts here already, and I think I’m very likely to continue to do so. I think it’s a rather good idea, and gets to the heart of a lot of different reasons for things.

Of course, there’s not going to be a single, simple answer for this kind of question. I’m going to propose two, which answer the question both specifically — why are we afraid of robots — and more generally, why we are afraid of the monsters we create in our own imagination.

And I’ve already found myself dividing this work into two posts, but that’s OK this time because it fits the two interrelated ideas.

So in this post, then, I’m going to look at how robots function as a container for all of our fears and anxieties about ourselves.

The next one will be how these robots come to represent how we, more specifically, fear what we are becoming in a post-industrial world.

Robots as a threat to (our) humanity

[See what I did there? The clever thing with the parentheses? a post-structuralist academic writing habit, that. A hangover from when I still wrote like a North American graduate student. I’ll explain more at the bottom.]

The overarching idea is that we are afraid of robots because of the existential threat they represent to our humanity. I do not mean by this, though, that we genuinely fear robots will arise armed with laser-cannon eyes to kill us all and wipe humanity off the earth in a genocidal apocalypse. Sorry. That makes for a good movie, but that’s not what I mean.

What I mean is that what robots represent a fear that we have of ourselves; who we are and what we’re becoming.

Freud’s notion of projection

I’m trying to be a little less shy about (re)using Freud [there’s that parenthesis again], because stripped away of the popular cultural perception (‘The guy that says we want to have sex with our Moms??’), I think Freud is still very relevant and gives us some really powerful ways for thinking about and understanding, narratively, how humans work. And there’s no better Freudian concept than his idea of ‘projection’.

Projection for Freud is one of the defence mechanisms that we use to help us cope with the anxiety that we feel. It’s a way of coping. It’s a very big idea with a lot of implications and applications, but I’ll try to limit myself here to the most relevant for our immediate purposes.

When we’re faced with negative feelings or thoughts, we imagine splitting off those negative parts of ourselves and we ‘project’ them away, to keep them far away from ourselves, so we don’t taint what we’d like to think of as our inherent goodness. Often, when we expel — or ‘project’ — these bad things, we expel them away into something else, like a person, an object, or even a symbol or an idea. That thing then becomes a sort of container for these projections.

We split off and project bad parts of the self — violent fantasies, hatred, for example — so that we can think of ourselves as pure and all good. The container of those projected bad thoughts, on the other hand, becomes the source of that badness. The container becomes a menace, threatening us, haunting us, because no matter how hard we try to disguise the truth, we know all of those bad thoughts are our own, really.

The classic example of this is the scapegoat. This goes back to the tradition laid out for the Day of Atonement in the Old Testament (Leviticus 16, for those of you who want to follow along in today’s catechism lesson), where a literal, actual goat, imagined to be carrying the sins of the community, is banished to the wilderness. This is an enactment of the idea of projection, where the negative things (our sins) are split off from ourselves, projected onto something else (the goat) and then chased far away, carrying all of our sins with it.

We can see scapegoating replay itself throughout history, which is why it’s such a useful term. Like in racism, for example. It is not we who are violent; it is them. They hate us and are out to get us. This is the root of paranoia. The belief that we are hated, or that we are being persecuted, is our own fantasy. They aren’t really sending people over to kill us. (In fact, that’s what we’ve often done to others.) They don’t hate us, because of our ‘freedom’ or because of anything else. We imagine they are like this because it’s us that thinks this way, really.

I need to add one point, just to lay down a marker for a future post: Sometimes, good parts of the self are projected into containers for safekeeping. An example of this is seen in cultural phenomena such as nationalism, for example, where people project their positive qualities (say, resilience, or hope) into a symbol, or an idea, or a leader. When a number of people all identify with positive qualities projected into the container, that container — the leader, the party, the idea — becomes a point of collective cohesion, a group identity. (This is called ‘projective identification, which is one of the most powerful post-Freudian ideas, but something we’ll look at in the next post.)

Robots as containers

So, back to the negative parts of ourselves.

This is how we imagine monsters more generally. Vampires, zombies, immigrants, Communists, trans-women… all the things that people find really scary, are just containers where we project our negative parts of ourselves.

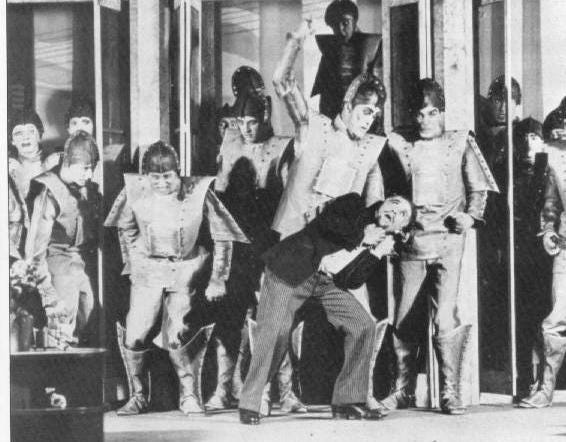

And we can include robots in this list. But robots are a special case. Robots started their lives in our imagination (remember R.U.R.) as something more akin to slaves. They are more like us. But as they evolved to look more like machines — in some cases literally empty metal boxes — they took on some unique characteristics.

The humanoid robot is transformed into a menacing, persecuting figure that becomes a container for all of our own negative emotions – the hate and violence of the robot is our own hate and violence that we imagine is out there, characteristic of these monsters instead of ourselves.

We can see examples of this projection/container narrative at work in so many popular robots, in the press and, especially, in our science fictions. The Terminator is always a good one to look at, or Star Trek’s Borg; they are, among other things, projections of our own, very human, violent fantasies projected onto something else. Robots don’t seek to commit genocide or to take over the world. [Not yet…I hasten to add. Just in case.] Historically, it’s humans that do this sort of thing. But as we’d rather not admit this to ourselves, we imagine that it’s something else, something other than us, that has all of these horrible ideas. So we imagine that it’s robots that want to do this to us.

Another terrific example can be seen in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Phillip K. Dick’s novel that is the basis of Ridley Scott’s 1982 film, Blade Runner. (If you haven’t read it, I can’t recommend it enough. Both the film and the book. But — controversial opinion this — the book is better.)

In DADOES?, the main character, Rick Deckard (played by Harrison Ford in the film), is a bounty hunter, the epitome of the ruthless, solitary assassin. But Deckard nevertheless believes that the humanoid robot – the ‘andy’ – is ‘a solitary predator’. This projection is a defence mechanism; it protects us from those parts of ourselves we’d rather not face. It protects Deckard from the knowledge that is more painful to admit, that he is the inhuman, solitary predator that kills without emotion or remorse. (Though, of course, Deckard is more… complicated.)

The inhumane commitment to violence, Dekard tells himself, isn’t his own — it’s the andys, The Killers, who are violent; it is their impulses that must be restricted. ‘Rick liked to think of them that way,’ the narrator tells us, ‘it made his job palatable.’ These projections allow Deckard to reason that his own violence, the ‘retiring’, or murder, of the andys, is the only rational response to such seemingly external violence.

It is in these contexts that robots represent an existential threat to us. We know that they are just these versions of ourselves, unconsciously. But when we fail to see this fear and anxiety and violence as our own and imagine instead that it originates from the robot, the robot becomes our creation not only in its physical construction but also in its ‘programming’, if you will — not just the instructions that we give it how to behave, but in our imagination. Our own darkest impulses and fear become displaced onto the machine. We imagine that it wants to destroy us. It is the machine that is driven by insecurity to destroy what it thinks threatens it. It is the machine that seeks vengeance. It is the machine that is driven by lust for conquest and empire.

I’ll pause here because this segues nicely into my next point, about how we fear that these monsters come to represent how we fear what we are becoming: unfeeling machines. Come back for Part 2 soon!

Addenda: colons and parentheses and other clever games

To come back to this. Almost all academic titles for the last four decades have a colon. It’s a formula. You have Sexy Title COLON descriptive title that describes what your paper is actually about and bores your pants back on. I should start an Instagram account with the best ones. But I’m no less guilty than anyone else. The full title of this paper is ‘Freud, Frankenstein and our fear of robots: projection in our cultural perception of technology’.

Yes, I’m sorry. The alliteration is sort of a thing. ‘Monsters, Machines, Messiahs’. I toyed with making this my ‘brand’, you know? The Alliterative Academic, identifying the ideas and ideologies, composing captivating cultural criticism for conscientious crowds… but Tony advised me against it. (And so that’s another thing for which I owe him deeply.)

Also, the parentheses: you’ll have noticed it back at the top. It’s a way of saying two things at once, without saying it twice. It’s very clever, I assure you. You’re supposed to read the parentheses, and also not read the parentheses, and understand the paradox. Classics include: (an)other (m)Other (ir)rational… it is supposed to connotate how something is both one thing and the other.

It is also often used with ‘post’ as the parenthetical word. Like (post)modernism, (post)Marxism, (post)Freudian, (post)feminism, (post)humanism… I could go on. The point in these cases, similar to above, is to say that something is simultaneously one thing — it is modernist, or Marxist, or Freudian, or feminist, or humanist — and that it is also beyond that thing, acknowledging, however, that we can’t ever really get beyond that thing.

And sometimes the ‘post’ just means not. Like, post-Marxism isn’t (usually) really Marxist. And post-feminism is often not actually feminist at all.

Post-Freudian, on the other hand, can be very Freudian. Or not. But it usually refers to psychoanalysts who came after Freud. The degree to which they may or may not be ‘Freudian’ is complicated by all sorts of politics and the difficult problem of determining who can speak authoritatively about what is ‘psychoanalysis’ after Freud… but, as so often is the case, is for another day.