Why are we afraid of robots? Part 2 - Robots as what we fear we are becoming

A second post where I look again at some of my ideas as to why we are afraid of robots

SO, here I am quickly and smoothly picking up from my last post, looking at some answers I gave to the question, Why are we afraid of robots? In this post, I want to look at the second point from my academic paper on the topic.

Looking back, I knew what I meant when I started trying to explain this, but I think my explanation was a bit muddled. I think I can explain this more clearly now. I think we need to take a more ruthlessly historical view in this case. Stripped of Freud and the post-doc cultural studies language [remember, ‘Well, stop.’], I think we can summarise this point nice and concisely:

Robots represent the fear of what we are becoming

There it is, in a nutshell.

Or, if you’re a bit more pessimistic, we’re afraid that we’ve already become robots.

There’s a story here.

I think in the last hundred years or so human beings have had a good, long look at the kind of creatures we’re becoming and thought, crikey! It’s almost like we’re becoming like walking, talking, thinking machines, smart but unfeeling, rational but devoid of empathy, bent on committing genocide and global destruction and all sorts of horrible things, divorced from those very things that we used to think made us uniquely ‘human’.

Whether or not this is, strictly speaking, true — and it probably is a bit, and not in other ways — doesn’t matter. It’s the story we tell ourselves. Or one of the stories we tell ourselves. Which then leads to other ideas and other stories, all of which become part of who we are.

And to represent these ideas to ourselves we invented robots, because — let’s be honest — we humans like the drama. And sometimes we need a little push to understand even the most basic things about ourselves, something concrete we can point to that helps us understand what we’re saying.

Let me show you my working.

It’s not an accident that robots came into existence when they did. It was a little more than 100 years ago that robots were invented. And robots were not, as I always love to remind people, invented in a lab, but in our imaginations. Robots first appeared to the world on a stage in the Czech Republic in 1920, in Karel Čapek’s play, R.U.R. (Rossum’s Universal Robots). I wrote a piece for The Conversation about this to celebrate the 100th anniversary that you might want to check out, though I’m sure that story will make its way here at some point.

The idea of mechanical versions of human beings has existed for hundreds of years. Golems and ancient automata and The Mechanical Turk and the like. But the specific word robot and its specific associations emerged at a specific point in time in a specific historical context. Like the monster Mary Shelley gave us in Frankenstein, if we pay attention to the details, the specific origins, shape and nature of these monsters, it can tell us a lot about what these monsters mean to us, and what we’re trying to tell ourselves when we tell those stories.

(Shelley, incidentally, created two monsters, of course. The one you’re thinking about right now, the ugly beast with stitches in its face and bolts in its neck, the one played by Boris Karloff, the one that you remembered is called the monster? That’s one. But it’s not the real villain of the novel. The real monster in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the titular scientist, Victor Frankenstein. In Shelley’s Romantic world — which is still kind of ours, too, more or less — the mad scientist with a god complex brought down by hubris is the real monster. C. A. Rotwang, Eldon Tyrell, Elon Musk and all the rest. These specific versions of Faust have a special meaning that we need to pay attention to. And yes, I’ll be returning to this idea later, too.)

How did we become robots?

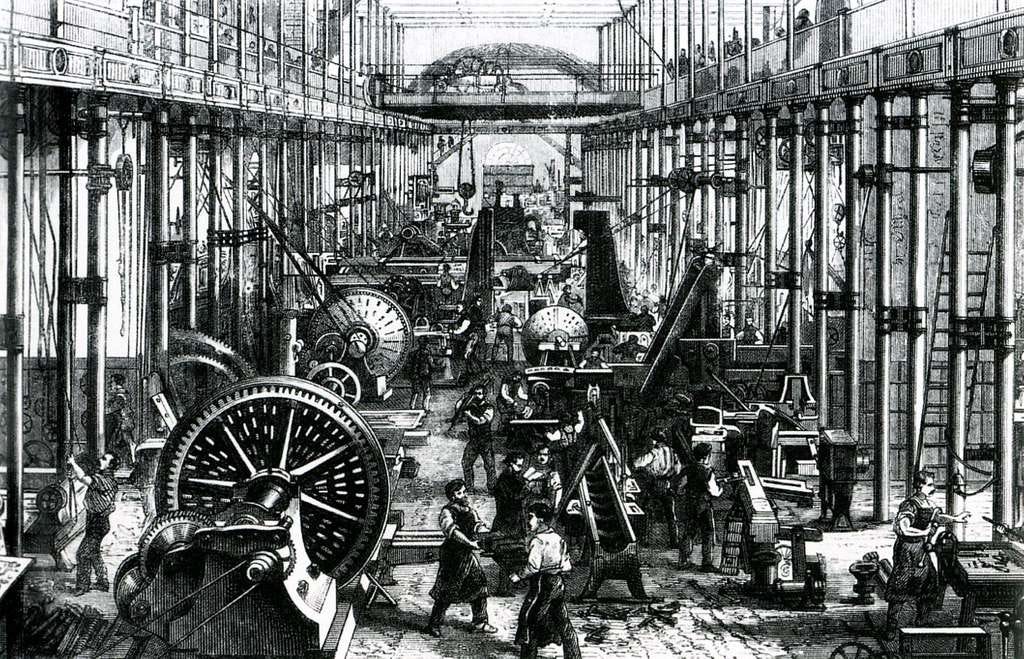

The history of how human beings have transformed into mechanical machines is a long one. We can, like Minsoo Kang in the excellent book Sublime Dreams of Living Machines, trace the entire history of the automaton in the European imagination, going all the way back to the Greeks, through the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. (And I do very much want to talk more about this book and its scope sometime.) But for our purposes here, we really only need to start examining what was changing for human beings in the Industrial Revolution around the late 18th century. By this time, we are already well into The Age of Reason, and there is a connection to a particular way of thinking about how we think, but it’s the mechanisation of the Industrial Revolution, and its connection to a new economic order, that really sets the stage for our transformation into robots.

This new economic arrangement changes our relationship with each other and with ourselves. Human beings start being sent into factories to function as mere pieces in a larger machine. This is if they are fortunate enough not to be replaced by those machines altogether. Does this sound familiar? We start to imagine that our choice is either to become a machine or risk being superseded by machines. In the new industrial age, we can either adapt or die.

Also at this time, we see the ambitious engineer, or wild-eyed scientist, start to replace the aristocracy haunting crumbling castles as objects of our fear. Later, in the twentieth century, this figure will transform again, subtly at first, into the merciless capitalist, who puts markets and profit above human emotion. But the people at the top are not alone in becoming divorced from their humanity: the emerging professional middle classes, armed not with hammers and sickles in their hands but engaging only their (disemodied) brains alone, sit behind desks, and have foreced to divorce their physical and mental selves, being governed by reason above any other morality or empathy.

All of this is painted in the broadest of brushstrokes, of course. But that’s fine. It’s not that details don’t matter. They absolutely do, and there is some terrific work that looks at some of the specific details for the whys and wherefores. But for what we’re talking about, broad brushstrokes are fine, because we’re talking about how these things turn into stories and become implanted in the human imagination over time. And sometimes our imaginations are less interested in facts and details than in perceptions.

Our fear of robots is, at least in part, a fear of our own rationality, that we ourselves are becoming emotionally detached, mechanical and calculating. Reason itself can be seen as a ‘monster’ in its own right: both the robot and reason are humanity’s own creations, inventions that we fear are becoming autonomous monsters more powerful than their creator. But it’s harder to ‘monsterise’ (I guess ‘demonise’ is better here) a disembodied thing. So we give it a body. We invent the robot.

(Which, as I explained in my last post, also functions as a container for us to put all this negative stuff. Because projections are important, and it’s important to have a place to put our projections. I’ll pick this up another time, too.)

Like so many of our monsters, from Frankensteins to andys to Terminators, the Borg, and even Wallace’s Wrong Trousers, we fear what we have created, and we fear that the process of construction – our science, yes, but also that science itself – will render us less human.

This is why robots look like us

Well, at the risk of getting all Marxist, mode-of-productiony in my analysis, robots also look like us because it’s easier to portray them, right? R.U.R. simply had actors on stage pretending to be machines. It was easier — and a lot cheaper — to tell an Austrian bodybuilder to pretend to be a robot than to actually do all the hard post-production VFX showing that he was a robot. But this is another reason why we imagine that robots already look like us: because we can so easily look like them.

Robots are often portrayed in film and literature as being at their most dangerous when they are indistinguishable from humans: again, recall The Terminator films, or Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?/Blade Runner, where the questions of who is flesh and who is a machine are paramount.

Deckard, in the novel Do Androids Dream?, longs to keep real animals, not mechanical imitations. The central fear of the book and the film is that there are androids living hidden in plain view amongst the human population and that we can’t tell them apart from ‘real’ humans.

But is the problem that we can’t tell the difference between humans and machines because the machines look so human, or because humans are starting to resemble so much machines?

Or maybe just that the space in between is getting harder to demarcate.

There is more to come soon on this, too, following on from this. Subscribe so you don’t miss it. And don’t forget that this is all free, so please do share with your friends and anyone you think might be interested in what I’m saying.

And finally, if you have any thoughts or comments, positive or negative, please do post them. I would very much rather these ideas become the start of conversations, rather than final words.